Appeals Court Interprets Chapter 91 License as Extending Private Way Over Lawfully Filled Land

The Appeals Court’s recent decision in Maslow v. O’Connor at first glance appears straightforward. The holding reiterates a familiar tenet of Chapter 91 licensing – that a Chapter 91 license doesn’t affect pre-existing property rights. But the result is quirky: in the name of preserving access to tidelands, the court in effect extends a private way over filled tidelands in which public trust rights (the right to “fish, fowl and navigate”) have been extinguished.

The basic facts in Maslow are:

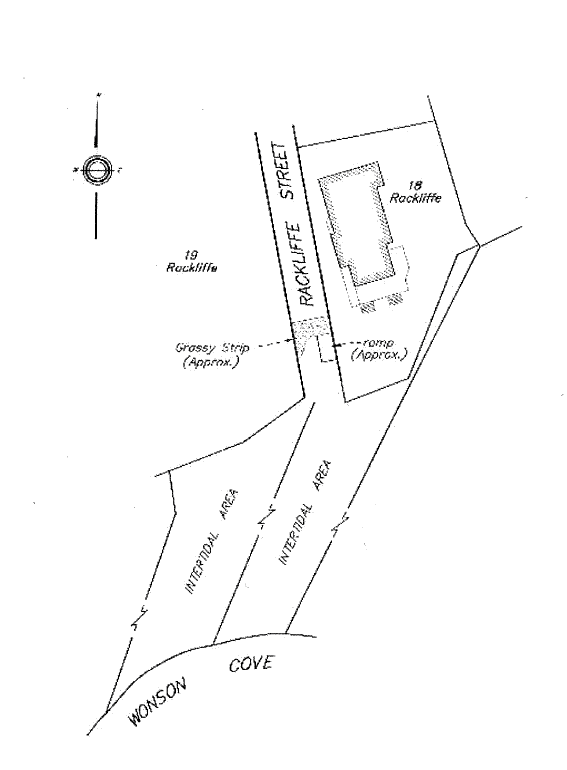

- Plaintiffs own lots abutting Rackliffe Street in Gloucester, which runs north-south and originally extended to the mean high water mark of Wonson’s Cove.

- Defendants own waterfront lots on either side of Rackliffe Street at its southerly end.

- In 1925, defendants’ predecessor was granted a Chapter 91 license authorizing her to build a seawall and place fill behind it, which created a strip of upland (the grassy strip) between the end of Rackliffe Street and Wonson’s Cove.

- Defendants hold fee title (one-half each) to the grassy strip

- Plaintiffs claim a right to pass over the grassy strip to reach Wonson’s Cove.

- The Chapter 91 license includes what is today (and presumably was in 1925) standard license language: “Nothing in this License shall be so construed as to impair the legal rights of any person.” It also states that it was granted “upon the express condition that no building or other structure be placed upon the filled area . . . .”

The Appeals Court held that the plaintiffs are entitled to traverse Radcliffe Street to its southerly end and continue from there over the grassy strip to reach Wonson’s Cove. The court’s holding rests on the two conditions in the Chapter 91 license that: (1) nothing in the license shall be construed to impair the rights of any person, and (2) no building or structure shall be placed on the filled area.

The court clearly wanted to put the abutters in the same position they were in before the Chapter 91 license, since before the filling and creation of the grassy strip the abutters had access over Rackliffe Street all the way to Wonson’s Cove. But, as the court acknowledges, under its own 2005 decision in Rauseo v. Commonwealth, the authorized filling “ended the public’s right to fishing, fowling, and navigation on the filled area and allowed the defendants to completely exclude the public from the filled area.”

What the court has done, then, is to extend a private way over a parcel of land – the grassy strip – in which (1) the defendants hold fee title, (2) the public’s Chapter 91 rights to fish, fowl, and navigate have been extinguished, and (3) the defendants are entitled to completely exclude the public. While the court justifies this result by citing the “no impairment” language in the Chapter 91 license (and similar language in Chapter 91 itself), the court has gone beyond simply “not impairing” the legal rights of any person: it has created a new legal right that didn’t previously exist – i.e., an access easement – over lawfully filled tidelands that are now privately owned. While from a practical standpoint this may be a desirable outcome, it seems to venture beyond any authority that could have been conferred by the license or the statute, and is untethered to any other authority or principle. Perhaps the same result could be achieved by considering this an easement-by-necessity scenario, but the Appeals Court doesn’t cite that doctrine or engage in the required analysis. Interestingly, the decision mentions that the abutters pursued a prescriptive easement theory at trial and lost on that claim – apparently they didn’t think they could rely solely on the “no impairment” language of the Chapter 91 license.

It strikes me that such an expansive view of Chapter 91’s “no impairment” language could have unexpected consequences, including – in situations like the one in Maslow – the creation of takings claims.